Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn't.

Mark Twain, Following the Equator: A Journey Around the World

As an academic, I spend a lot of my time thinking about the nature of truth, the base of evidence that academics marshal to make and contest truth claims, and the level of uncertainty that surrounds the making of truth claims consistent with the scientific method. This is not a new or startling claim, since the search for truth has long occupied the discipline of philosophy since ancient times and continues to occupy us today.

As a magician, I spend a lot of my time thinking about the role of deception. I have written before, that performance magicians occupy a continuum that ranges from an explicit contract with the audience to 'suspend disbelief' and enjoy the demonstration of many inexplicable feats to a more ambiguous and implicit contract with the audience that invites them to believe in supernatural power. Regardless of their position on this continuum, magicians deploy various forms of deception to achieve their desired effects.

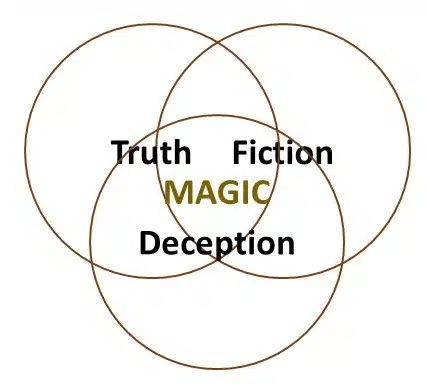

As an academic magician, I am keenly interested in the intersection between and among truth, fiction, and deception. My own performances carry with them an appeal to truth, the use of complete fiction, and the mechanics and methods of the conjuror to achieve the necessary means of deception to achieve a desired effect.

More importantly, I use magic and its deceptive nature to make a contribution to our understanding of truth. My performances have variously used magic to understand the truth about subversion; the role of language games and how human communities develop shared understanding; the role of doubt and how it might allow us to understand truth; the extent to which we may or may not have free will; how the science of deduction provides a way to discover truth; and how the history of Victorian mental institutions teaches us lessons about about social justice.

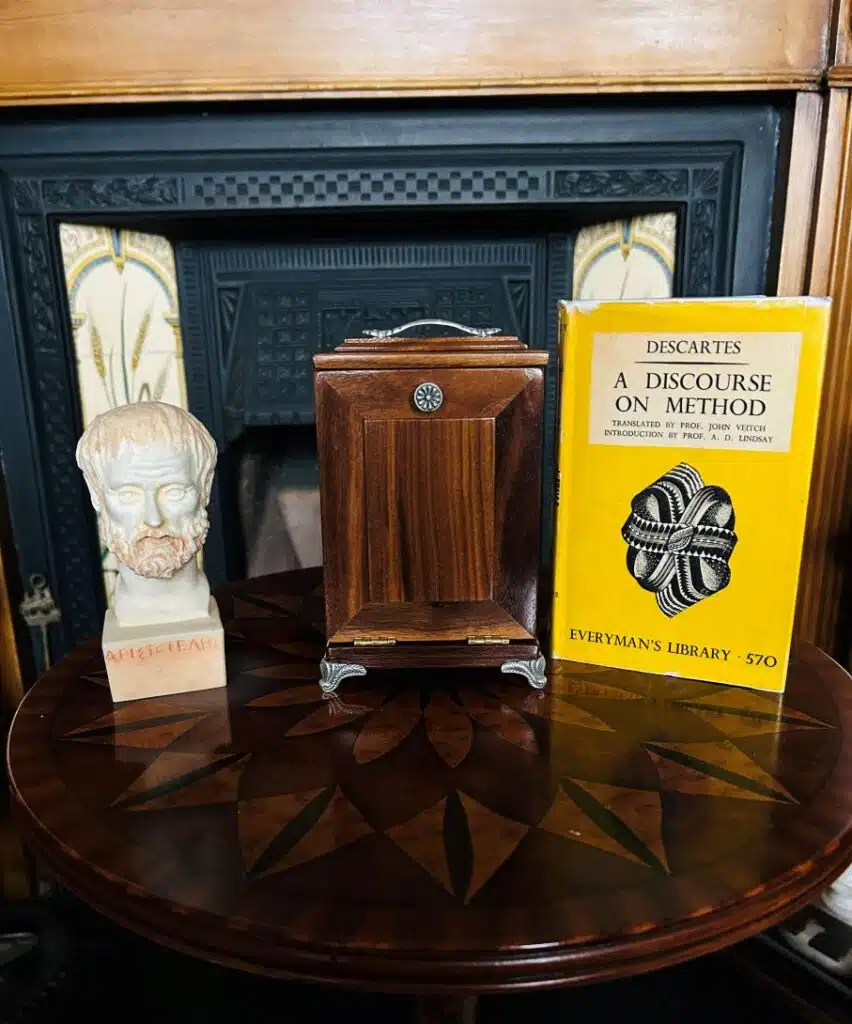

Consider the role of doubt. In his Discourse on Method, French philosopher René Descartes ruminates over whether his senses are deceiving him. He contemplates a ball of wax and does not know of any method for determining whether its true nature is a solid or a liquid. He questions the actual height of a tree outside his window. These and other doubts lead him to wonder what is the one true thing he can say if he engages in what he calls 'hyperbolic doubt.' His answer is 'cogito ergo sum,' or 'I think therefore I am.' For Descartes, the mere act of thinking undisputedly establishes his existence, an idea that has transformed the way we think about the world and our relation to it.

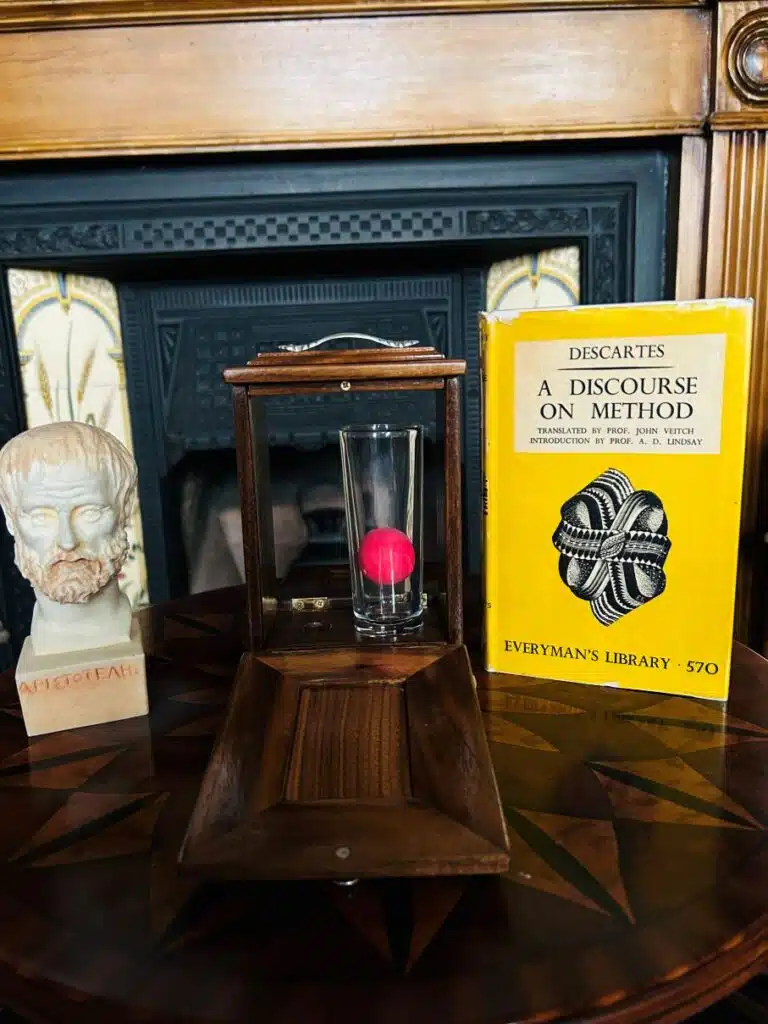

Now, consider how a magician might explore this truth claim. Imagine a philosopher's box, which contains two doors on either side, a small glass, and a ball sitting next to the glass. All these objects are shown to the audience, yet when the two doors are shut momentarily and then re-opened, the ball is now inside the glass. After this occurrence, the audience may freely examine the box, the glass, and the ball. What did the audience just witness? Are their senses deceiving them? Are they now willing to engage in hyperbolic doubt? If they do, what truth claim might they now be willing to make?

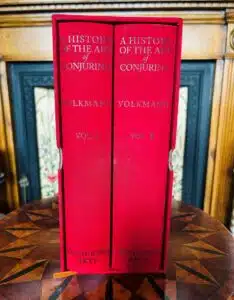

This example from my own repertoire illustrates the ambiguous location that magic occupies between truth, fiction, and deception. As above, this is nothing new in the history of magic. The publication of the new two-volume edition of The History of the Art of Conjuring by Kurt Volkmann shows us that this is indeed the case. His account in the book takes us back to the ancient origins of magic, which reside in the ever-evolving tensions and contestations between religion, philosophy, science, and magic.

Volkmann shows us that certain individuals in history lived in and navigated between these different worlds. He also demonstrates that in an effort to defend the human rights of women during the period of persecution of witches, Reginald Scot's 1584 publication of The Discoverie of Witchcraft was devoted to explaining how the inexplicable feats such women achieved were through pure deception, not the presence of evil or through the help of unseen demons. The feats did, however, enhance the public perception of their power. Scot's book is now lauded as one of the most significant manuals on magic.

This ambiguity between truth, fiction, and deception continues to occupy the time and attention of magicians. Many magicians are happy to use deception as part of a magic show, but unhappy to see the use of deception for other means, such as in psychic shows or by those professing to be fortune tellers. Indeed, Harry Houdini spent the last years of his illustrious career in magic seeking to expose fraudulent mediums.

My own form of performance magic sits comfortably within this history of ambiguity and my new show Truth explores the themes raised in this post. First, in Hevel, I combine magical deception and The Book of Ecclesiastes to explore three fundamental truths: (1) we are not able to stop the advance of time, (2) our lives are never free of chance, and (3) seeking to cheat death is like spitting into the wind. Second, in Our Dark Century, I explore the uncanny reality depicted in three major novels of the 20th Century: (1) Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, (2) 1984 by George Orwell, and (3) The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood.

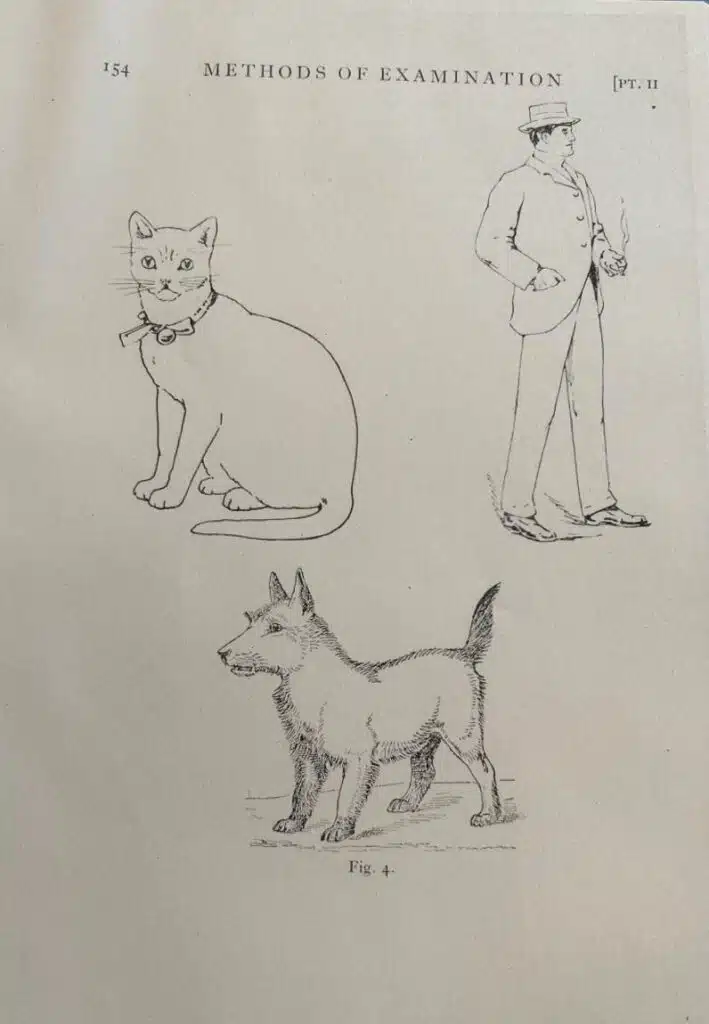

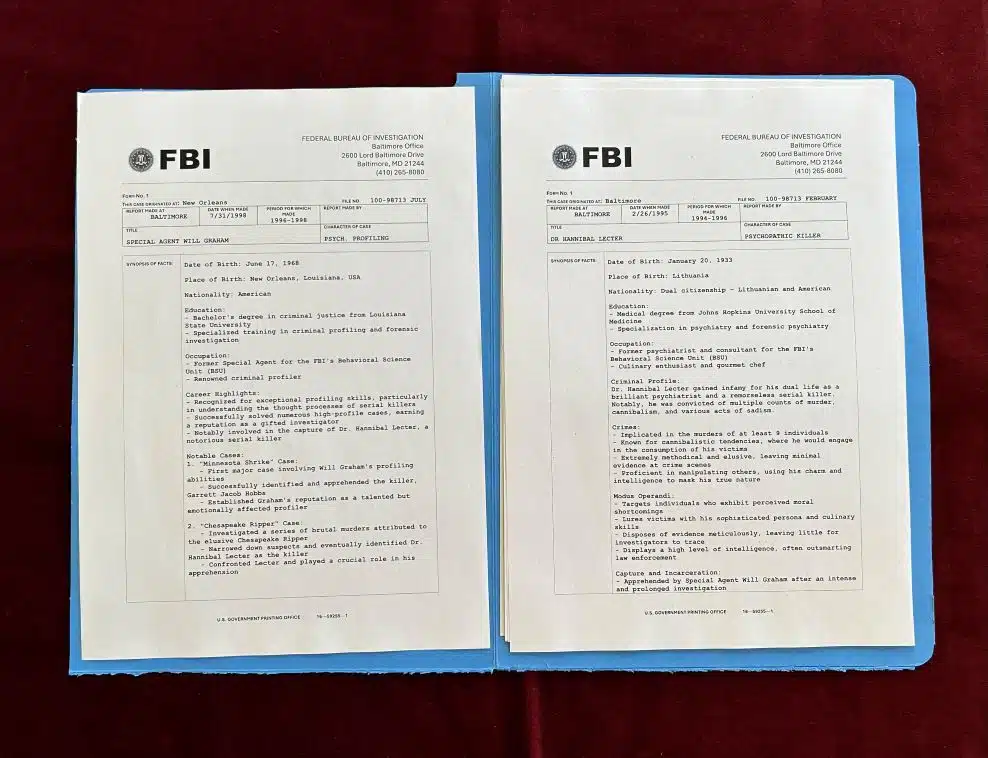

Finally, and perhaps most intriguing to me, I was struck by the first series of Netflix series Hannibal, in which special agent Will Grant takes part in the 'clock drawing test,' to assess his grounding in reality. The clock drawing test is one of many cognitive tests set out in Head's (1926) Aphasia and Kindred Disorders of Speech (Cambridge University Press).

Fascinated with these tests, Hannibal's Haunting engages one of my participants in a series of exercises involving objects, colours, pictures, words, physical tasks, and of course, the clock drawing test, the results of which may end up being somewhat unsettling, both for my participant and for the audience.

We now purportedly live in a 'post-truth' era full of 'alternative facts,' where truth, fiction, and deception continue to be inter-twined. Magicians continue to move amongst us in ways that challenge or sense of reality, while at the same time, yielding deep insights into truth, even if such insights are achieved through deception.

Contact

T 07584 615104

E info@todd-landman.com

Keep In Touch

Todd Landman. All Rights Reserved

A Mackman Group collaboration - market research by Mackman Research | website design by Mackman